ΓΛΩΣΣΟΛΟΓΙΑ-ΔΙΔΑΚΤΙΚΗ

Decoding ‘noisy’ language in daily life

Study shows how people rationally interpret linguistic input.

5 Oddities Of Everyday Language That Leave Experts Baffled

Say the word "butter" out loud. You can whisper it if you're in public, but I don't know if whispering "butter" is really that much better than just saying it loud and proud. If you're an American, there is an extremely high chance that you didn't say the hard "t" sound in the middle, but something like a quick tap, making it sound more like "budder." OK, so tell me why you did that.

What Do We Use Language For?

Language is central to all our lives and is arguably the cultural tool that sets humans, us, apart from any other species. And on some accounts, language is the symbolic behaviour that allowed human singularities—art, religion and science—to occur.

The Sounds of Speech

Identifying Words

When we speak we say words and when spoken to we hear words. In normal discourse, however, we do not separate---the---words---by---short---pauses, but rather run one word into the next. Yet in spite of this we still hear utterances as composed of discrete words. Why should that be so?

A clue is provided by the fact that in order for us to hear the words, the utterance must be in a language we know; in utterances in a language we do not know we do not hear the words. Similarly, when we hear a string of nonsense syllables, we cannot tell whether it is composed of one or of several words. Knowledge of language is therefore crucial.

In a way this is not surprising. Everybody who has studied a foreign language knows that learning the words is a major part of mastering the language. Knowing the words is not sufficient, but it surely is necessary. When we learn a word we store in our memory information that allows us both to say the word and to recognize it when said by someone else. And the reason we do not hear words when spoken to in a foreign language is that we have not learned them, we do not have them in our linguistic memory, i.e., in the part of our memory dedicated to language.

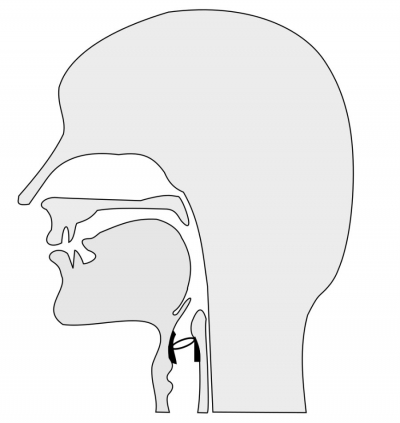

Speaking

A plausible account of an act of speaking might run as follows. Speakers select from their memories the words they wish to say. They then perform a special kind of gymnastics with their speech organs or articulators, i.e., with the tongue, lips, velum, and larynx. The gymnastics results in an acoustic signal that both the speaker and the interlocutors hear. Since in performing the gymnastics speakers do not pause at the end of each word, the words in the utterance run into one another. This model of speaking is represented graphically below:

Words in memory>>> Articulatory action>>> Acoustic signal

There is some evidence that when we hear speech the same process is activated but in reverse An acoustic signal strikes our ears; we interpret the signal in terms of the articulatory actions that gave rise to it, and we use this interpretation--rather than the acoustic signal itself--to access our memory.

Consider now the gymnastics that we execute as we pronounce the English words 'meet' and 'Mott'. In both words we begin with an action closing the oral cavity with the lips and end with an action by the tongue blade closing the oral cavity at a point in the anterior region of the hard palate. Between these two actions is an action of the tongue body: The tongue body is raised and advanced in 'meet', and lowered and retracted in 'Mott' without, however, closing the cavity. The production of these words is, thus, made up of distinct actions by three distinct articulators. The actions must, moreover, proceed in the order indicated: If the order of the three actions is reversed, different words are produced, viz., team, Tom. Facts of this kind motivate the hypothesis that the words we say are composed of discrete sounds or phonemes.

Words in Memory

As noted above, words are learned and are stored in our linguistic memory. If the words we utter are composed of discrete sounds, then it is reasonable to suppose that words in memory also consist of sequences of discrete sounds. Scientific study of language strongly supports this supposition although the evidence and argumentation are too complex to be given here.

In uttering a word we actualize the sequence of discrete sounds stored in memory as a sequence of actions of our articulators. Because, like other human actions, speaking is subject to limitations on accuracy, it is to be expected that there will be some slippage and that the discreteness of the sounds will be compromised to some extent in the utterance. In fact, X-ray motion pictures of speaking show that the actions of the articulators in producing a given sound do not begin and end at exactly the same time. This slippage, however, does not interfere with the hearer's ability to identify the words--i.e., to access them in memory. Inertia of the articulators is, of course, not the only factor in the failure of the speech signal to reproduce accurately various aspects of the word as represented in memory. Other factors are rapid speech rate and a variety of memory lapses.

In spite of the fact that burps, yawns, coughs, the sound made in blowing out a candle, and many other noises are produced by actions of the articulators, they are not perceived as sequences of phonemes, even though they may be indistinguishable acoustically and articulatorily from utterances of phoneme sequences. Not being words, these noises are not stored in the part of our memory that is dedicated to words. By hypothesizing that only items stored in the linguistic memory are composed of phonemes, we explain why burps, yawns, etc. are not perceived as phoneme sequences.

In sum, speech sounds are the constituents of words, and words are special in that only words are sequences of speech sounds.

Linguistics in Everyday Life

Language use is an essential human ability: Whether it's telling a joke, naming a baby, using voice recognition software, or helping a relative who's had a stroke, you'll find the study of language reflected in almost everything you do. Linguists spend their days seeking answers to questions like the following and so many more, because language and linguistics play such a fundamental role in every human's life.