Darwin’s theory of evolution was once heralded as the best idea that anyone has ever had. T.H. Huxley, the foremost biologist of his day, said: ‘How stupid of me not to have thought of it!’ I suspect that many of us have thought likewise when we fail to spot the seemingly obvious.

That was certainly my reaction when I discovered the ‘Simple View of Reading’, first proposed by Gough and Tumner in the 1980s (Gough & Tumner, 1986). Surprisingly, the importance of the Simple View of Reading was a blind spot in our vision on the teaching of reading that went unrecognised in England for years.

In 2005, however, in pursuit of a conceptual model for our Review of Early Reading (Rose, 2006), I benefitted immensely from advice on the simple view of reading, and much else, from two eminent Professors – Morag Stuart and Rhona Stainthorp. In consequence, the Simple View of Reading became a key feature of our Review. How well this seminal insight has since been promoted in teacher training, and in framing school and national policies for teaching reading, remains uncertain.

This article argues for a deeper understanding of the Simple View of Reading and how it has transformed perspectives on what it takes for beginners of any age to become fully-fledged readers capable of achieving high standards of literacy.

As with Darwin’s theory of evolution, the Simple View of Reading was not an outcome of prior research so much as a ‘eureka’ insight borne of intelligent imagination and careful observation. Since its inception, moreover, the Simple View of Reading has developed apace: we now know that it may be simple but it is by no means simplistic. It has generated a great deal of research that confirms its basic equation:

Reading Comprehension = Decoding x linguistic comprehension (R=DxLC)

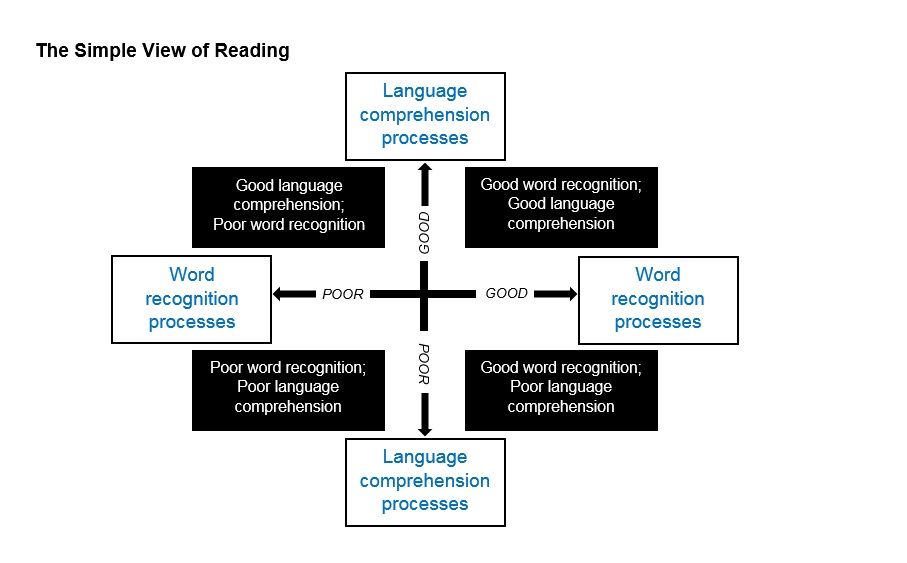

The Simple View of Reading differentiates between two dimensions of reading: Word recognition processes and Language comprehension processes. It makes clear that different kinds of teaching are necessary to promote word recognition skills from those needed to foster the comprehension of spoken and written language, which is the goal of reading. Though considered separately, both dimensions are essential to reading. It is of first importance for teachers of reading to be clear about which of these two dimensions their teaching aims to develop, and make sure each of them is taught explicitly.

Further, the Simple View of Reading helps teachers to assess children’s reading performance and progress in each dimension, and to recognise that, given their different but developing abilities, they will not all progress at the same rate. The uneven status of children’s reading in a typical primary school class can be mapped in quadrants:

This goes some way towards helping teachers establish the ‘Goldilocks conditions’ for ‘optimal teaching’. That is to say, teaching which is neither too easy nor too hard for children as they learn to read – or as a teacher of six-year-olds once said: ‘We need to get the reading porridge just right for them to thrive on it.’

In recent years, much research has sought to identify the vital ingredients of the reading porridge. The broad consensus is that there are five, key, interdependent elements which must be secured and taught thoroughly for a reading programme to be effective.

Briefly stated, the Simple View of Reading avers that learning to read requires two abilities – correctly identifying words (decoding) and understanding their meaning (comprehension). Acquisition of these two broad abilities requires the development of more specific skills. An extensive body of research on reading instruction shows that there are five essential skills for reading and that a high-quality literacy programme should include all five components:

- Phonemic awareness. The ability to identify and manipulate the distinct individual sounds in spoken words;

- Phonics. The ability to decode words using knowledge of letter-sound relationships;

- Fluency. Reading with speed and accuracy;

- Vocabulary. Knowing the meaning of a wide variety of words and the structure of written language; and,

- Comprehension. Understanding the meaning and intent of the text.

There is some debate as to whether a sixth element, notably, ‘oral language’, should be added to this list, or whether the promotion and enrichment of oral language is best seen as a crucial, overarching aim of the whole curriculum from the early years onwards.

From research to the classroom

The teaching of reading is by no means unique in seeking to apply the findings of authoritative, high quality, research to establish ‘what works best’. The route from research to the classroom, however, is often problematic in making the key messages accessible and clear to those who are expected to apply them, notably, frontline teachers.

Experience teaches that important messages from research may be lost in translation – or rather, like Chinese whispers, they become increasingly distorted by misinterpretations. Only a fool would believe, for example, that phonics is the ‘be-all-and-end-all’ of learning to read. It would be equally foolish, however, to ignore the fact that an overwhelming amount of leading-edge research now strongly supports the message that a thorough grounding in phonics is essential but not sufficient to becoming a skilled reader.

In our language system, children must learn how the alphabet works for reading and writing – ‘the alphabetic principle’. To this end, an emphasis on one key element of the Simple View of Reading, notably, decoding, has been necessary to restore the alphabetic principle to its essential place in teaching beginners to become skilled readers. The downside of this, however, has been a ‘phony war about phonics’. This has fuelled an anti-phonics lobby, much to the disadvantage of children, especially those who struggle to learn to read, and despite the fact that: ‘… studies of reading development, studies of specific instructional practices, studies of teachers and schools found to be effective – converge on the conclusion that attention to small units in early reading instruction is helpful for all children, harmful for none, and crucial for some’ (Snow & Juel, 2005, pp. 501–520).

It is not only phonics, of course, that has fuelled fierce debate about reading. Equally controversial in recent times, some would say, is the issue of how best to help children deemed to be dyslexic. Attempts to segment and define the various elements of reading failure have raised questions about the term ‘dyslexia’, whether it exists and, if so, to what extent.

Though beyond the scope of this article, it is worth noting that the Simple View of Reading strongly supports the view that dyslexia is essentially a word-processing problem. The highly respected researcher David Kilpatrick has suggested that the first diagnostic question when a teacher says a student struggles with reading should be: ‘What if you read the passage to him, would he understand it?’ As Kilpatrick points out: ‘Simply defined, dyslexia refers to a difficulty in developing word-level reading skills despite adequate instructional opportunities’ (Kilpatrick, 2015). This, of course, prompts the question: how adequate were the student’s instructional opportunities? In other words, was the teaching inadequate? If so, how can it be improved?

Considerable progress has been made on mapping the complex warp and weft of dyslexia – neurological and otherwise. Mark Seidenberg, another leading-edge researcher into reading who has contributed hugely to the discourse on dyslexia comments: ‘The condition may be complex, but the by-product of this deeper understanding is the realisation that there are both more opportunities to prevent reading impairments and more ways to address them should they develop than earlier theories allowed’ (Seidenberg, 2017, p.168).

This suggests that dyslexia may not be immutable. We need to travel in the faith that it is within the reach of a breakthrough despite the limitations of our current knowledge. Meanwhile, we would do well to remember that science insists that ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’ and ‘correlation is not the same as causation’. Good science challenges consensus, and the nature of good research is to beget more research into the as yet unknown elements of learning to read as all else.

All of which underlines the importance of making sure that we spell out, and continue to update, the line of best fit from research and proven practice, so that teachers are not left feeling that they are at the mercy of rows and rows of backseat drivers pointing in different directions.