—but there are many more lesser-known but critically important aspects that demand our attention as educators. While Black history should be taught year-round, Black History Month provides us with a unique opportunity to elevate the stories and voices of Black people who have shaped American history.

As a literacy consultant who understands that elementary teachers have time for only one read-aloud a day at most, I suggest selecting books that can serve a myriad of purposes. In February, that means reading books—like those that follow—that teach Black history and can also serve as mentor texts to inspire students to try new craft moves in their informational writing.

28 Days: Moments in Black History That Changed the World, by Charles R. Smith, illustrated by Shane W. Evans

Smith highlights both well- and lesser-known events, laws, and people in Black history. There’s a 29th day—for leap years—dedicated to helping readers understand that they too have the power to shape history. Every entry has a distinct structure, including a eulogy for Madam C.J. Walker and a poem for Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe.

Mentor text possibilities:

How do you teach someone about a big topic in a meaningful way? We instruct students to narrow their focus. Smith makes Black history accessible by covering important events and people briefly. Ask students to select main and subordinate ideas using tools like boxes and bullets to facilitate this work.

The graphic style of 28 Days is worth emphasizing. Students will be inspired to tinker with using different fonts, point sizes, and colors after closely studying this text.

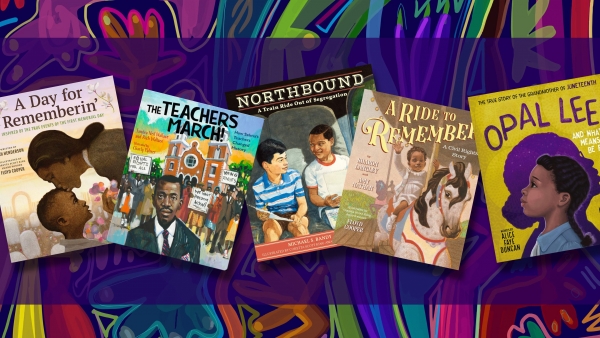

A Day for Rememberin’: Inspired by the True Events of the First Memorial Day, by Leah Henderson, illustrated by Floyd Cooper

This story follows 10-year-old Eli on what is regarded as the first Memorial Day, in 1865. Readers can feel the significance of the day as a dressed-up Eli misses school to join his parents in paying their respects to the Union soldiers who gave their lives in the Civil War.

Mentor text possibilities:

It’s important for students to learn that leads and endings aren’t just the first and last sentences—they can span several pages. By studying leads and endings in picture books, students come to understand that authors have more than one strategy to open or close a text. For instance, I’d categorize the lead in A Day for Rememberin’ as a Meeting the Characters lead, which provides readers with an introduction to main and secondary characters.

Students can study the font treatment, which helps writers communicate their words more effectively—giving them the opportunity to highlight words or phrases. This book shows students how they can utilize italics. Henderson uses italics to emphasize significant words and to embed lyrics in the text, helping readers hear them as songs.

Northbound: A Train Ride Out of Segregation, by Michael S. Bandy and Eric Stein, illustrated by James Ransome

After watching trains pass by his family’s farm for years, young Michael Bandy is taking his first train trip. He befriends a White boy on the train during an interval when the “Colored Only” signs come down, only to be ushered back to his segregated car later.

Mentor text possibilities:

The heart of a story is often revealed bit by bit. Here, Bandy and Stein employ a variety of techniques—action, internal thinking, dialogue, setting details, character details—modeling for young writers how to stretch out the most important parts of their own text.

If you’re teaching students how to write narrative nonfiction, it’s possible they’ll craft stories that require additional information to be understood. Including back or end matter helps readers better understand the historical context of a book that would feel out of place in the narrative. The authors’ note in Northbound discusses the Interstate Commerce Act, which impacted the way segregation was enforced on trains.

Seeds of Freedom: The Peaceful Integration of Huntsville, Alabama, by Hester Bass, illustrated by E.B. Lewis

Seeds of Freedom illustrates how the Black citizens of Huntsville sought justice through peace in their remarkable fight to integrate their city. Through planning and actions like lunch counter sit-ins, the seeds of freedom were sown. Readers witness the fight for the integration of Huntsville’s schools—the first all-White public schools in Alabama to admit Black children.

Mentor text possibilities:

This book takes place over the course of 21 months. Showcasing the way Bass uses headings can teach students how dated headings can frame their writing, marking changes in time and place.

The author employs words like segregation and integrate as well as helping young readers understand their meaning along the way. One way to offset definitions within a sentence is to use dashes. By showing students examples of how to define words in text, you’ll help them embed content-specific language into their writing.

Opal Lee and What It Means to Be Free: The True Story of the Grandmother of Juneteenth, by Alice Faye Duncan, illustrated by Keturah A. Bobo

Activist Opal Lee—who marched from Texas to Washington, D.C., at 89 years old to bring attention to Juneteenth—believed it was crucial to remember the past in order to have a better future. Readers learn about the origins of Juneteenth as well as what life was like for Black Americans in the years that followed.

Mentor text possibilities:

Writers create a mood by making conscious decisions about punctuation. Duncan, for example, creates voice in her text by skillful use of commas, ellipses, and hyphenated compound adjectives. By teaching students these moves, we can help them make purposeful choices so their writing sounds the way they intend.

Some of the back matter in Opal Lee is traditional, like a Juneteenth timeline and a source list. But there’s also a recipe for the red punch lemonade that’s featured in the story. As a result, students can explore the back matter and think of a variety of additional things they could include after the last page of their main text.

A Ride to Remember: A Civil Rights Story, by Sharon Langley and Amy Nathan, illustrated by Floyd Cooper

A Ride to Remember transports readers to Maryland’s Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in the early 1960s. This first-person narrative details the joyous day that Sharon Langley became the first Black child to ride the carousel—coincidentally, on the day Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Mentor text possibilities:

Authors often employ multiple strategies to open a text. Within the first two page spreads, this book combines a character snapshot with an invitation to imagine the beauty and equality of a carousel ride. Showing students leads that use multiple strategies will encourage them to take writerly risks.

A Ride to Remember contains multiple sentences that model a variety of comma uses. Since students are at different points of comma understanding, try leading a variety of strategy lessons that meet them where they are.

The Teachers March!: How Selma’s Teachers Changed History, by Sandra Neil Wallace, illustrated by Charly Palmer

The Teachers March! describes the genesis and organization of a teachers-only march in Selma, Alabama. Rev. F.D. Reese knew that teachers were pillars of the community and believed that if he could get Black teachers in Selma to march—in an effort to obtain the right to vote—then change would follow.

Mentor text possibilities:

One of the ways that Wallace keeps readers engaged throughout the text is by inserting questions, which make the reader stop and think about the information they’re learning—something students can learn to do in their own work.

Quotation marks are often used around a word or a phrase to set it off or emphasize it. Students can tinker with using quotation marks for more than dialogue by using them to stress selected words or phrases in their writing.