When a man is given three years to live at 21, and he dies 55 years later, it shouldn’t come as a shock. But though I’m 15 years younger than Stephen was, and he had been gravely ill for years, if you knew him you couldn’t help thinking that he would always be around, that his life force was inexhaustible, that he would always have another miracle to pull off.

The scientific community rightly makes much of one of his miracles, a discovery he made in 1974 of something now known as Hawking radiation: the phenomenon in which black holes — so named because nothing can escape them — actually allow radiation to get out.

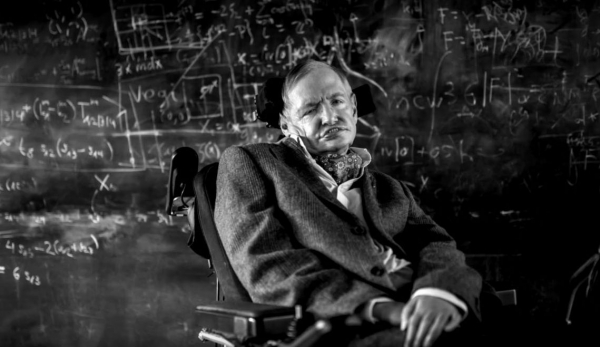

In popular culture Stephen was another kind of miracle: a floating brain, a disembodied intellect that fit snugly into the stereotype of the genius scientist.

But to me Stephen was also the everyday miracle of an ordinary embodied human — albeit one who had to battle in heroic ways within the confines of his particular shell.

What you don’t often hear about Stephen is that he loved a good curry, but not if it was spicy. That he considered himself allergic to gluten, but that he wouldn’t notice when his caregivers occasionally let some slip through. That he ate bananas mashed with kiwi every day. That he had to eat all his food mashed or chopped, and had to be spoon-fed. And that he never let this embarrass him, even when he ate in the finest restaurants.

I began collaborating with Stephen in the early 2000s, not long after I had published my first book. He contacted me to ask if I’d consider working with him on a book — the first of two we would write together. Though I was also a physicist, and had had the good fortune to work alongside other geniuses of the field like Richard Feynman, I was no less awe-struck by the chance to get to know Stephen.

Soon we were collaborating, literally elbow-to-elbow, many hours each day, for days on end. We would talk and debate about physics, and about how best to write about it. But I was also helping to dab his face dry, adjust his glasses, carry him to the couch. And then we’d get back to arguing. With time, our intellectual connection was deepened by that physical intimacy, and we grew close.

Since Stephen couldn’t speak, he communicated through his computer. Composing a sentence was like playing a video game — the cursor would move on the screen, and he would have to capture the letter or word he wanted by pressing on a mouse with his thumb, or, in his later years, moving his cheek to activate a motion sensor in his glasses. When he was done, he would click an icon and his famous computer voice would read what he had typed out.

Stephen could compose his sentences at a rate of only about six words a minute. At first I would sit impatiently, daydreaming on and off as I waited for him to finish his composition. But then one day I was looking over his shoulder at his computer screen, where the sentence he was constructing was visible, and I started thinking about his evolving reply. By the time he had completed it, I had had several minutes to ponder the ideas he was expressing.

This was a great help. It allowed me to more profoundly consider his remarks, and it enabled my own ideas, and my reactions to his, to percolate as they never could have in an ordinary conversation.

When I argued a point of physics with Stephen, I always lost. I would scribble equations on a pad or a whiteboard, trying to sway him, but when I was done, I would find that the answer was the one he had already worked out in his head.

He was no less certain in his ideas about how to write our books, though when we disagreed on those matters, there was no right or wrong answer, only preference. And so we might argue at length — on one occasion we did so for two hours — over a single sentence.

There was an important difference between us here. Making my arguments took little effort. To oppose my ideas, Stephen had to struggle to type every letter of every word. Yet it was I, not he, who ceded points out of exhaustion. Once, during a particularly heated discussion, I waited several minutes for him to respond, and then, when his response finally came, it was a joke. Even when contemplating the cosmic, he had a keen sense of the comic.

Stephen’s expertise was gravitation, the weakest of the four fundamental forces of the universe. Yet Stephen himself was a strong force. When, as a student, he started his work on black holes, most scientists thought it was a dead-end field. His doctors made a similar assessment regarding his prospects in life.

Proving people wrong turned out to be his strength — and his gift to all of us.

By LEONARD MLODINOW