In stress-timed languages such as English, stresses occur at regular intervals. The words which are most important for communication of the message, that is, nouns, main verbs, adjectives and adverbs, are normally stressed in connected speech. Grammar words such as auxiliary verbs, pronouns, articles, linkers and prepositions are not usually stressed, and are reduced to keep the stress pattern regular.

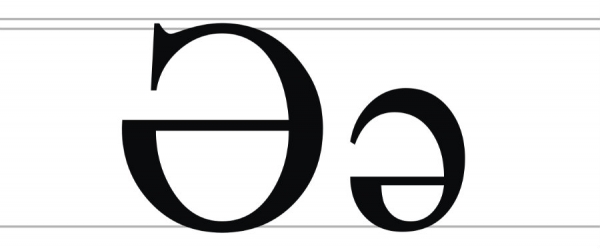

This means that they are said faster and at a lower volume than stressed syllables, and the vowel sounds lose their purity, often becoming a schwa. Listen to these two examples of the same question. The first is with every word stressed and the second is faster and more natural with vowels being reduced. The same thing happens with individual words. While stressed syllables maintain the full vowel sound, unstressed syllables are weakened. For example, the letters in bold in the following words can all be pronounced with a schwa (depending on the speaker's accent): support, banana, button, excellent, experiment, colour, sister, picture.

Why I teach the schwa

To understand the concept of word or sentence stress, learners also need to be aware of the characteristics of 'unstress', which include the occurrence of the schwa. In addition, if learners expect to hear the full pronunciation of all vowel sounds, they may fail to recognise known language, especially when listening to native speakers. Even if they understand, students often do not notice unstressed auxiliaries, leading to mistakes such as, 'What you do?' and 'They coming now'. Helping your students to notice the schwa won't necessarily lead to an immediate improvement in listening skills or natural-sounding pronunciation, but it will raise their awareness of an important feature of spoken English.

How I teach the schwa

- Fast dictation

I find this activity useful for introducing the schwa in context. However, it can be repeated several times with the same group of students, as it also recycles grammar and vocabulary.

Warn students that you are going to dictate at normal speaking speed, and that you will not repeat anything. Tell them to write what they hear, even if it's only one word. Then read out some sentences or questions including language recently studied in class.

For example, I used these questions with Pre-Intermediate level students, following revision of present simple questions:

- How many brothers and sisters have you got?

- How often do you play tennis?

- What kind of music do you like?

- What time do you usually get up?

- How much does it cost?

After reading the sentences, allow students to compare in pairs or groups. Then read again, while students make changes and additions, before a final comparison with their partner(s). Next, invite individual learners to write the sentences on the board, while others offer corrections. The teacher can correct any final mistakes that other learners do not notice.

Say the first sentence again naturally, and ask learners which words are stressed. Repeat the sentence, trying to keep stress and intonation consistent, until learners are able to correctly identify the stressed syllables. Then point to the schwa on the phonemic chart and make a schwa sound. Get students to repeat. Read the first sentence again and ask learners to identify the schwa sounds. Repeat the sentence naturally until students are able to do this. Ask them to identify the stress and schwas in the other sentences, working in pairs or groups. My students found the following, although again there is some variation between accents.

- How many brothers and sisters have you got?

- How often do you play tennis?

- What kind of music do you like?

- What time do you usually get up?

- How much does it cost?

N.B. I normally get learners to write the schwa symbol underneath the alphabetic script.

Once this is done, you can drill the sentences, perhaps by 'backchaining'. This is where the sentence is drilled starting from the end, gradually adding more words.

Try to maintain natural sentence stress when drilling. A danger of focusing on the schwa is that it can be given too much emphasis, so correct this tendency if it occurs in individual and choral repetitions.

After doing this activity for the first time, I ask learners some awareness-raising questions:

- What kinds of words are stressed? (Content words, i.e. nouns, main verbs, adjectives, adverbs)

- What kinds of words are generally not stressed? ('Grammar words', i.e. auxiliary verbs, pronouns, articles, linkers, prepositions)

- Do stressed syllables ever contain schwa? (No)

- Do you think this is more important for listening or speaking? (Students will often say 'speaking' but in fact this is more important for what Underhill calls 'receptive pronunciation': learners will still be understood if they give all vowel sounds their full value, but it's worth practising these features orally to help learners 'develop an ear' for them.)

- Stress and schwa prediction

- Take a short section of tape or video script (a short dialogue or a few short paragraphs of spoken text). Before listening or watching, ask learners to identify the stressed syllables and schwas, and to rehearse speaking the text. They then listen or watch and compare their version with the recording. There will probably be differences, but this can lead to a useful discussion, raising issues such as variations in the use of schwa between accents, and emphatic stress to correct what someone else has said.

- Word stress and schwa

- I often ask learners to identify word stress and schwa in multiple-syllable words recently studied in class. This recycles vocabulary, and illustrates the point that schwa does not occur in stressed syllables. It also helps with aural comprehension as well as correct pronunciation of these words.

- A gentle reminder

- You may still find, even when drilling, that learners are tempted to pronounce the full vowel sound in unstressed syllables. I give my students a gentle reminder that schwa is the 'Friday afternoon' sound. Slumping in the chair and looking exhausted while saying schwa normally gets a laugh!

Conclusion

Many of my students have seemed fascinated by the insight that English is not spoken as they thought, with every vowel being given its full sound, and after an initial introduction to the schwa they start to look for it themselves in other words and sentences. More ambitious students take every opportunity to practise this 'native-speaker' feature, while others revert to the full vowel sound after drilling, but in either case their expectations of how English sounds will have changed.