Scientists have just published a startling analysis of commonly used words in 4298 languages (62% of all those spoken). They wanted to find out if there were associations between particular sounds and meanings that couldn’t be put down to the fact that the languages were related, are used close to one another, or to chance.

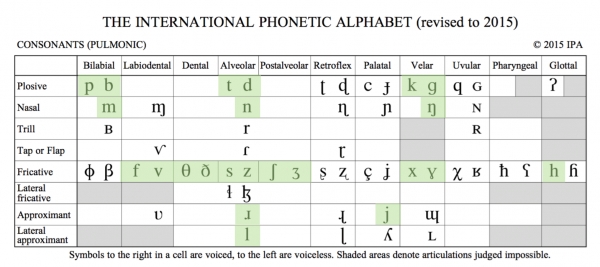

As it turned out, they detected strong correlations between sounds and meanings that were independent of genetic relationship, borrowing or coincidence. For example, words for “small” often contained high front vowels (roughly, “ee” as in “peak” or “see”); words for “round” and “red” were linked to “r” sounds; words for “star” to “z” and words for “full” to bilabial consonants (“p” and “b”). Associations were found for body parts: “tongue” was correlated with “l” and “nose” with “n”. Remember, these similarities were found in languages as distant from one another as English and Tagalog, Yoruba and Mandarin.

Why does this matter? One of the first things a student of linguistics learns is that the relationship between the signifier (the sound of a word) and the signified (the concept it represents) is arbitrary. We use the word “tree” to signify a plant with a trunk and leaves, but there’s nothing particularly tree-like about the combination “t-r-e-e”. If a law was passed saying we had to call it “frave” instead, that word would gradually become normal, just like “ki” is for Japanese speakers and “umthi” for Xhosa.

This is part of what gives human language its immense productive power. New words can be coined and they don’t have to be tied in any way to the concept they represent. Just the convention linking that sound and the concept in people’s minds is enough.

There are some exceptions: onomatopoeic words like “smash” or “judder” have physical qualities which do slightly resemble the things they describe. But the idea that this “sound symbolism” extends much further than a few childish curiosities has long been dismissed by most linguists.

Damian Blasi and his colleagues focussed on 30 fundamental concepts – none of which represent loud or distinctive noises, often fertile ground for onomatopoeia. These came from the famous “Swadesh list” of 100 basic words, and included “bite”, “drink”, “ear”, “leaf”, “we”, “tooth”, “skin”, “one” and “stone”. Incredibly, as well as positive links, they uncovered sets of sounds these words seem to “avoid” – ones that appear much less often than you would expect if it were down to chance. “Water” (strangely enough for English speakers) seems to avoid the “t” sound. Words for “tooth” avoid “b” and “m”. The “a” “h” and “r” sounds are found less commonly in words for “breasts”.

The study builds on earlier research which hinted at non-arbitrary relationships between sound and meaning. For example, people have been able to successfully pair up words that have opposite meanings in languages they don’t know. One study showed that English speakers could make better-than-chance guesses at the concreteness of unfamiliar foreign words – that’s to say, whether a word might mean something like “car” versus something like “happiness”. Intimations, if you like, of a universal language of sound.

That leaves us with the question: why? In the 19th century, the founder of modern linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure, made arbitrariness the central plank of his theory of language. His insights are still pretty powerful. But as the science developed, it seemed to become more and more divorced from the world in which language is used, and the bodies and minds that use it. This trend culminated with ideas about a genetically encoded “language module” in the brain, possessed of a language-specific set of rules that determine not just the structure of English, but of Swedish, Burmese, Kazakh, Czech, you name it.

Those schools of thought are identified with theorists such as Stephen Pinker and Noam Chomsky. Others believe that language isn’t necessarily hived off, that its structures are determined by an interplay of forces that include general principles of cognition, logical relationships (like cause and effect) and shared environment.

Blasi et al, for their part, say that the explanation must lie in “factors common to our species”, which leaves things fairly open. They point out the association of “nose” with nasal sounds and “tongue” with “l” sounds – saying that a link between body parts and the sounds they make has been noted before. “Breasts” are associated with “m” and “this might be due to the mouth configuration of suckling babies or to the sounds babies produce”.

So far, so not particularly mysterious – although the embedding into actual language of these properties is extraordinary if you think about it. But what about “leaf”, “star”, “round”, “red” “water” “we” and “you”? There are clearly some missing pieces of the jigsaw. Synesthesia in both the narrow and broad sense is one possible answer – “the ability that humans have for associating stimuli across different modalities” as the authors put it.

In other words, translating the “feel” of a leaf or a stone or a star into sound. That’s pretty much what poets do. And, as it turns out, there could be more poetry woven into language than we ever realised.