Lorena Germán remembers positive moments in her years as a student in U.S. public schools—joyful lunch breaks she spent with her peers, intense intellectual debates they had while reading The Odyssey—but when she reflects on her educational experience overall, the word “hostile” comes to mind.

“Some teachers did not really respect me or my peers—they didn’t believe that we really could engage in legitimately critical and thoughtful conversations,” says Germán, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic who grew up in the U.S. and is now a middle school teacher.

Germán still remembers how one high school teacher ignored her for the rest of the school year after she spoke up in a board meeting about being mistreated in school. The hostility in education, she says, “shows up when teachers don’t believe in us and then penalize us for who and how we are.”

Yet those formative years fueled Germán’s motivation to become a teacher in order to dispel the hostility she had faced and foster a more welcoming classroom for all students through open conversations about race, privilege, and societal conflicts. In her many roles—chair of the National Council of Teachers of English’s Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English, cofounder of #DisruptTexts and Multicultural Classroom, pedagogy chair of EduColor—Germán is a vocal advocate for culturally sustaining pedagogy and is committed to helping other English language arts teachers grow more culturally conscious through inclusive materials and curricula.

In her new book, Textured Teaching: A Framework for Culturally Sustaining Practices, Germán proposes four principles for classroom engagement: flexibility, interdisciplinary design, experiential learning, and a student-driven and community-centered approach.

Germán and I chatted about the vision for social justice teaching articulated in Textured Teaching and the current state of anti-bias teaching in K–12 classrooms.

HOA NGUYEN: With social justice teaching at the core of Textured Teaching, you write early in the book that social justice tends to be a vague term. How would you define it?

LORENA GERMÁN: Social justice has become this buzzword all over the place and certainly in education. Anything now can be called social justice, and that’s not accurate because it is just justice at the societal level. To me, social justice is working toward a redistribution of resources, opportunities, wealth, and power that promotes equity.

NGUYEN: Why is it important that teachers agree on a common understanding of social justice?

GERMÁN: We’ve seen the problems with having conversations about racism, for example, when people do not have a shared understanding of what it is. If somebody thinks racism is simply an interpersonal act of meanness, then we cannot have a conversation about racism at a structural level, right? We need to have a shared understanding of concepts so that we can talk about the same issue—not in the same way, but at least about the same thing.

NGUYEN: You write that Textured Teaching aims to teach students to spend time in the “gray space,” where they can discuss social issues from various perspectives. Could you elaborate on what this gray space means for students?

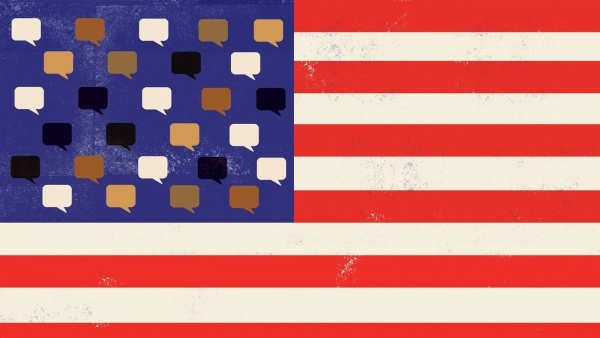

GERMÁN: The gray space, I think, is reality. It’s fair to say that we’re very polarized, but in my opinion we’re actually a little less polarized than it seems. I don’t mean the simple binaries of the left or the right. There are people who might be closer to the center in some areas, whether it’s voting, morality, or social expectations of themselves and others.

We are not one-dimensional beings, right? Human beings are multidimensional. And so I think we actually live a little bit more in the complication of gray than black-and-white. And I don’t mean that simply about race, I mean issues in general.

And so I think that it’s OK for us to question how classroom literature, math, and science can help us think critically about where we stand on these issues. What good is it for me to know addition, for example, if I can’t use it to make my community’s life better and not simply to get a good job to make money? We’ve seen that that’s not the end-all-be-all. It does not lead to self-fulfillment and improvement in life.

NGUYEN: We’ve witnessed a lot of pushback this year from a number of states, teachers, and parents about whether anti-bias and anti-racist teaching has a place in K–12 classrooms. As someone who’s active in the space, how do you respond to that?

GERMÁN: Silence has never helped us solve any problems. We saw that with the rise of the #MeToo movement, when everyone is saying, “Yeah, that’s happened to me too.” Then that unearths tensions and difficulties and pain that was unnecessary in the first place.

We’ve seen that happen with race, too—that’s pretty cyclical in this country. Every five, 10, or 20 years or so, we have this “racial awakening,” if you will, particularly of some White people who are like, “How did we get here? This is not the America I know.” The current wave of banning of books and silencing difficult conversations in schools isn’t new. You can look back at the civil rights movement and even before then, too. We’ve seen this historically happen throughout U.S schooling, and it never wins.

We should be able to say, “Hey students, slavery was a real thing. Race is this, bias is that, prejudice is this other thing, and sexual harassment looks like this. OK, now let’s move forward together.” This way, you have a more educated body of racially literate and culturally competent people who can engage with people who are different from them in a respectful, humane way.

We cannot pick and choose the conversations we want to have—either we have them all, or we have none.

NGUYEN: Sometimes people can get really caught up on questions like, “Why are you teaching my children critical race theory?,” when I think most teachers from preschool through 12th grade would agree that this isn’t what’s happening in their classrooms.

GERMÁN: I’m sure there are people who have learned about critical race theory and use it in their own approach to instruction. But no one is coming into a prekindergarten classroom or a third-grade classroom and saying, “Let’s talk about what doctors Bell and Crenshaw and Delgado designed in this particular book, positioning critical race theory....” Come on now.

If we cannot say that White people are the beneficiaries of White racial hierarchy—if we can’t have honest conversations about the fundamental truths of our society like our own country’s racial history—we can’t really talk about anything. We cannot pick and choose the conversations we want to have—either we have them all, or we have none.

Before all these attacks were happening, this wasn’t such a contentious subject, and it was more comfortable to teach about these issues. But now, with all this tension, is the time we need teachers to step up and do the work.

NGUYEN: In Textured Teaching, you talk about being a teacher of color in a predominantly White school. What has been your personal experience navigating the various scenarios you’ve taught in?

GERMÁN: In spaces where I was the only person of color in the classroom, there were power dynamics at play and this tug-of-war between the teacher and the parents for control and authority in that space. You’ve got to be careful about what you discuss in there, how you approach that conversation, what pace you move at.

When I was writing this book, I was teaching at a private, independent school in Austin, Texas, that’s pretty progressive both politically and socially. There were times when people trusted my credentials, my education, my background, my expertise.

On the other hand, there were moments where my students said very hurtful things and I was just like, “Wow. I can’t believe you really just said that or genuinely had that belief.” But it’s so important for us to remember that this is a young person and not an adult, and the classroom is the space where they can process and work against such beliefs.

There were days when I had to step away, go home, and just have some ice cream. When you’re doing a lot of this work, you’re unearthing biases every day with young people, and sometimes it really gets to you.

NGUYEN: I suppose being so involved in the space means that there would be a lot of discomfort in the classroom—a lot of tension and a lot of stress...

GERMÁN: ...but a lot of growth, like when my daughter gets knee pain and hip pain when she’s having a growth spurt—I think about what that growing pain looks like in the classroom. People get hurt in the process. But if my classroom is a gray space, then we need to interrogate that pain a little because we’re having conversations about important things that are impacting real people, you know? I want to make sure that people understand that, yes, there will be discomfort and struggle—but it’s a beautiful struggle.