Concerned about equity issues, they didn’t want their students to feel uncomfortable if they lacked access to a private space or were embarrassed by their home environment, for example.

“The Covid‐19 pandemic has already increased college student anxiety and depression, and a mandate for camera use may add to that trauma,” they reasoned in a new study. But by the end of the year, the duo realized that they might have struck the wrong balance. Faced with a sea of blank screens, they often wondered whether they were talking to themselves. How were their off-screen students reacting to challenging material?

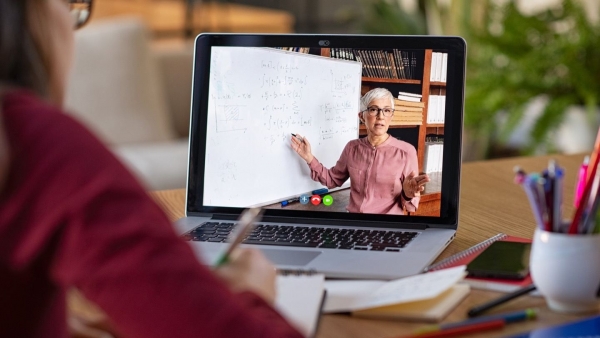

While the professors wanted to respect student privacy, the lack of ambient feedback when the Zoom camera was off-put a real damper on learning. “Instructors benefit from receiving nonverbal cues from their students such as smiles, frowns, head nods, looks of confusion, and looks of boredom, so that they can evaluate their teaching in real-time and adjust accordingly to improve student learning,” Castelli and Sarvary write—emphasizing the value that comes from being able to read students’ faces.

Students, too, benefit from being able to see each other onscreen. In the study, a majority indicated that “using videoconferencing helped build trust and rapport with other students and helped them to develop a sense of identification with others in their group.” The social context of living classrooms—the often invisible human connection that reinforces learning—was missing for students, who insisted “that being able to hear and see each other in real-time helped construct a ‘more complete picture of their peers.”

If both sides of the educational equation were losing out, then a middle ground needed to be found, the professors thought—one that respects the rights of students but supports the social dynamics of learning, at least in some situations.

To refine their strategies around camera use, Castelli and Sarvary surveyed hundreds of students to identify their main privacy concerns. The students, it turns out, weren’t staying off-camera for the anticipated reasons. Forty-one per cent of students said they turned their cameras off because they were “concerned about [their] appearance”: They had messy hair, were wearing pyjamas, or hadn’t yet showered, the study reported. Relatedly, 17 per cent of students felt that everyone was watching them, creating a sensation of unbearable self-consciousness.

Equity-related issues also cropped up. Underrepresented minorities were twice as likely to be concerned about their homes being visible and were 12 percentage points more likely to cite a weak internet connection—perhaps a reflection of how the pandemic can exacerbate the digital divide.

QUICKLY ESTABLISH A NORM

Being proactive about cameras early on can be an easy first step to establishing the norm—more so than during the school year if a camera-off culture has set in.

That’s because virtual classrooms—and the expectations that follow—may be new to most students. In the study, one in 10 students didn’t turn their camera on simply because they felt that was the norm. “If you don’t explicitly ask for the cameras and explain why, that can lead to a social norm where the camera is always off,” Castelli and Sarvary warn. It can quickly become “a spiral of everyone keeping it off, even though many students want it on.”

To counter this, Castelli and Sarvary recommend including the camera policy in the class syllabus and explicitly encouraging camera use on the first day of class. A camera-on norm can also help address the main reason why students turned their cameras off: concerns about their personal appearance. If students anticipate being seen on camera, they’ll be more likely to brush their hair and dress appropriately.

TEACHER-TESTED STRATEGIES TO ENCOURAGE CAMERA USE

Addressing norms doesn’t mean that students will turn the camera on daily—you’ll still need to make accommodations for students, and you’ll need to encourage the camera used contextually.

For Liz Byron Loya, a visual arts teacher in Boston, encouraging students to turn their cameras on has its roots in building a positive community, not in expecting compliance from students.

“Focus on trust, both teacher to student and student to student,” writes Byron Loya. “Students who know they are safe and cared for by their community will be more comfortable having their cameras on.”

Icebreakers and games—Pictionary and charades come to mind—can help ease students into turning their cameras on, especially if they feel that the focus is less on them and more on the activity.

Byron Loya also offers specific tips for encouraging students to turn their cameras on:

Survey students to identify barriers preventing them from participating.

Remind students that they can use a virtual background if they don’t want to show what’s happening behind them.

Encourage students who have the social capital to use their cameras.

Enable the waiting room and greet students one by one as they enter your virtual class.

Use Zoom’s “Ask to Start Video” feature to invite students to turn their cameras on.

For students who are reluctant about giving a live presentation, provide an option to submit a prerecorded video.

For students who request to keep their cameras off, high school teacher Katie Seltzer holds camera-optional Socratic seminars. “Students in the outer circle, who typically would be evaluating the participation of their peers in the inner circle, used the chat feature to echo powerful comments they heard and ask questions of the inner-circle group,” writes Seltzer. There’s no stigma associated with having their cameras turned off since the activity allows them to fully participate in a way that mirrors the activity in traditional in-person classrooms.

Alex Shevrin Venet, a community college teacher and former school leader at an alternative high school in Vermont, believes that the key to encouraging students to turn their cameras on starts with the teacher. Model mistakes and try to be authentic, she suggests, and let students know that it’s OK to be themselves on video.

“Don’t worry about sounding rehearsed or making your space look Instagram-perfect,” writes Venet. “Embrace the fun and silly moments when pets and family members make guest appearances. Create an environment where students recognize that turning cameras on means laughter, making silly faces at friends, and being seen for who they are.”