Three middle-school-aged boys draw pictures in chalk on a blackboard on a bright Saturday afternoon. “Write the word below the drawing,” I say. The word apple goes under the apple, tree under the tree. Afterwards, they practice with vocabulary flashcards for a half hour. At a bathroom break, all three bolt down the hall in search of a soccer ball, teasing each other in Arabic.

They might be eager to learn English, too—but I feel I’ve lost them already.

The three are recent arrivals from war-torn Syria and have been in the country for only a year. Though the civil war has raged since 2011 with more than 400,000 casualties and millions of refugees, these boys bear the little obvious impact of the traumas they’ve been through and the elaborate screening process it took to get here—and we don’t ask. In many ways, they seem like average tweens, enthusiastic and eager to learn.

As a teacher of high school English, I’ve decided to volunteer at an English as a second language (ESL) Saturday tutoring session, a program established in response to the growing community of refugees here in Jersey City. Despite my years of experience in the classroom, I’m finding out what ESL teachers everywhere know: that teaching English as a second language to students with varying levels of preparedness is a complex, and often stressful, endeavour. Good intentions aren’t enough.

AMERICA'S FUTURE CLASSROOMS

Newcomer English language learners (ELLs) with interrupted educations have distinct challenges—among them jumping into an upper grade with few formal school skills, living in households with unstable incomes, or coping with buried traumas—but in many ways, they mirror the future of classrooms in America.

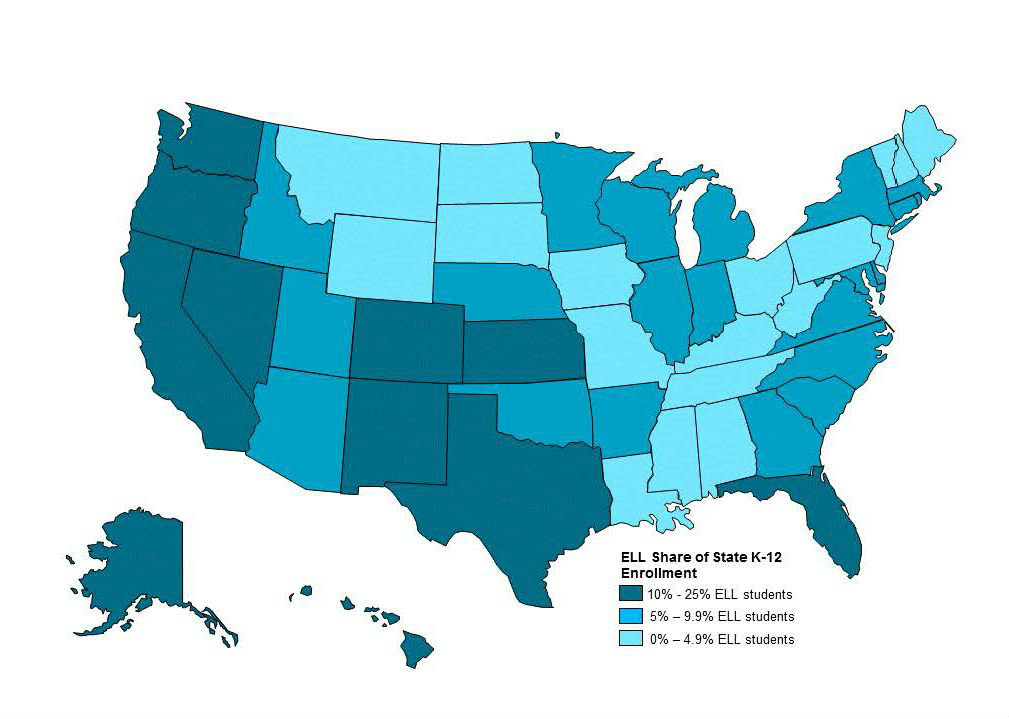

Nearly one in every 10 U.S. students is now an ELL, the fastest-growing population of students in the nation. A full 42 per cent of those with limited English fluency immigrated here from outside the U.S., many after attending school in another country for years, according to the Migration Policy Institute, a research organization focused on migrant and refugee trends.

The impact on the U.S. school system has been vast. From coast to coast, in both large cities like Los Angeles and smaller towns like Troy, Michigan, and Lewiston, Maine (population 36,000), there has been an influx of ELL students and families who speak a bewilderingly wide range of languages—from Creole to Tagalog and Urdu.

Understandably, schools are struggling to comprehend the scope of the issue and provide timely solutions. For teachers on the front lines like me, answers aren’t coming fast enough. Research on the topic is limited, and many of the recommended pedagogies for teaching in a classroom with a wide range of languages and proficiency levels are new and untested. And the added pressure of helping students, especially older ELLs, meet grade-level content standards can feel like salt in the wound.

There are some promising efforts in the works, though. A few districts have created separate schools solely for ELLs, while others have opted to offer bilingual instruction as early as preschool. Many have responded by hiring more ESL teachers and adding full immersion classes where ELLs learn alongside native English speakers. And in a handful of states, including New York, Arizona, and California, every teacher is now required to have coursework or professional development in teaching English as a second language.

But I’m thinking back to my kids—the third grader who hadn’t learned to grasp a pencil and the outwardly confident ninth grader who was hesitant to expose his difficulty reading aloud. I started teaching English as a second language with very little to go on, just optimism in the sponge-like minds of the students and simple, seemingly obvious tips like “speak slowly” and “use visuals.”

There must be a better way. So I set out to find what experts and other schools suggested for teaching ELLs.

SET HIGH EXPECTATIONS, SAN FRANCISCO

The experts I talked with agree that it’s critical to keep expectations high for ELLs—even if at first they seem unattainable.

“What traditionally has happened for ELLs in many systems is that they are not afforded or invited to participate,” explained Maria Santos, a director at the research group WestEd and co-chair of the Understanding Language project at Stanford University. “There are some systems that say once they get enough English, then they can enter core academic courses. We are saying, ‘No, they have to be involved from day one.’”

At San Francisco International High School, all students are non-native English speakers and take regular high school classes that use teaching techniques specifically geared toward ELLs. The school is dedicated solely to newcomers but is just one of many options for students who are still learning English in the highly diverse, 56,000-student San Francisco district—a “multiple pathways” approach representative of the options available to ELLs throughout other states.

While experts such as Santos recommend that ELLs be integrated with native English speakers in regular classrooms, San Francisco International High School teachers say that for many older newcomers, a school devoted solely to ELLs provides students the support they need to build confidence as they continue to learn both English and academic content.

Critical to the mission of San Francisco International is the notion that every teacher is a “teacher of language” who embeds English language learning within a traditional high school curriculum, rather than separately, says the principal, Julia Kessler. “Our students don’t have time to learn English and then do high school.”

And, just as importantly, when a student struggles, teachers still give them assignments that keep them challenged.

“If the student doesn’t have the language to read the New York Times article the rest of the class is reading, that doesn’t mean give them a children’s book,” Kessler says.

MEET STUDENTS HALFWAY, NEW YORK CITY

When those high expectations meet with tailored instruction, new English learners can pick up both content and language skills with surprising speed. In a recent session of Christopher Benson’s AP U.S. History class at Marble Hill High School for International Studies, a public school in the Bronx set high above the Harlem River, students reviewed for an upcoming test by going over sample AP questions.

At one table, I observe four girls discussing a text by George Washington warning against the rise of political parties. “What does sectionalism mean?” one girl asked. “It’s like dividing,” another answered. When the whole class reconvened, students discussed a historian’s interpretation of Columbus—deciding to agree with an answer from a student who did not speak English just three years ago.

Half of all students at Marble Hill High School are English language learners and 90 per cent are low-income, yet 93 per cent graduate within four years. Last year, the school was highlighted by Stanford University’s Understanding Language group as one of six “schools to learn from.”

The teachers go all the way to make sure you understand things.

At Marble Hill, all teachers receive training in strategies for ELLs. Staff members regularly review data together to catch any students in need of extra support and help ensure students grasp concepts by focusing lessons on grade-level skills and then modifying content to address any language gaps.

In an inclusion ninth-grade biology class for ELL and native English speakers, for example, a teacher helped students write up a lab report by providing a worksheet with prompts suggesting an appropriate verb or chemical substance, much like in Mad Libs. In a history class, the teacher used T-charts and sentence stems to help students develop a strong thesis for an essay about the French Revolution.

The teachers and the community building at Marble High are key reasons students say they select and stick with it.

A junior named Luis, who arrived from the Dominican Republic as a freshman and spoke no English, said the first school he tried in the district was “like a jail,” and he didn’t learn much. “At Marble Hill High, several teachers stay after school to work with students,” he says.

“The teachers go all the way to make sure you understand things,” adds Mohamadou, a senior.

GET THEM TALKING, NEW JERSEY

In my Saturday class, Arabic is the lingua franca, although a few students only speak Tigrinya, a language spoken in Ethiopia and Eritrea. Students begin at varying levels and then come and go depending on the week. We never know how many might show up. To keep them returning, we offer rides and try online sign-ups and text message reminders.

But we’ve also had to consider what newcomers might want from an English language class, which could be as something as simple as talking to them about things they know and care about, say educators like Darren Chase, an ELL teacher with New Design High School in New York City.

As the main ELL teacher for around two dozen students, Chase says he tries to get his students talking about anything he can—breakfast, the weather, sports—so they keep practising their language skills.

It’s so easy for an English learner to hide in the margins and get home and realize they spoke no English that day at school.

“It comes naturally to a teacher to want to talk and explain, but it’s important to turn around that dynamic for ELLs,” says Kessler. “It’s so easy for an English learner to hide in the margins and get home and realize they spoke no English that day at school.”

So in a recent Saturday class, my colleagues and I put aside the flashcards and coursebooks, and instead give the students' sample dialogues to help them write their own conversation scripts on a topic of choice.

One boy writes about shopping for soccer gear with his favourite professional player, who suggests buying goalie gloves as well as cleats. I ask questions about the details while helping fill in words when he struggles to finish a sentence. In between, we talk about an Egyptian fish restaurant around the corner. He and his friends tell me it’s good, but not like food from Syria.

The oldest boy in the class chimed in, explaining that the Egyptians in Jersey City must have had to leave their country because they “did bad things,” he says, as he searches for the precise words to explain power, discrimination, flight, and exile.

It strikes me then that one day this student could become a politician, a lawyer, or anything he wants—once he learns his new language, he’ll have the words to describe his own history, and a better chance to plot the course of his own future.

By Carly Berwick